Beginning a strength training program is a significant step toward enhancing overall health and athletic performance. It improves muscular strength and endurance, supports bone density, and promotes long-term metabolic health. Many teen athletes, however, begin training with the expectation of rapid muscle growth and defined abs within weeks. In reality, the body undergoes a series of internal adaptations long before visible changes occur. Understanding these adaptations—particularly those involving muscle development, nervous system efficiency, and adipose tissue changes—can help set realistic expectations and encourage long-term commitment.

How the Body Adapts to Strength Training

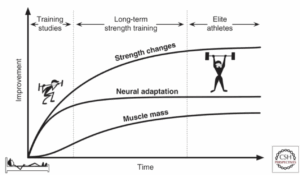

The body’s response to resistance training occurs in two key phases: neurological adaptations and structural changes, such as muscle hypertrophy and adipose tissue remodeling.

Phase 1: Neurological Adaptations (Weeks 0–6)

During the first several weeks of training, most strength gains come from improvements in the nervous system, not muscle size.

- Enhanced Motor Unit Recruitment: The nervous system becomes more efficient at activating motor units (a motor neuron and the muscle fibers it controls), allowing more fibers to contract simultaneously.

- Improved Movement Coordination: Neural pathways refine, resulting in better control and safer, more effective lifting.

- Reduced Neural Inhibition: Protective mechanisms (such as those mediated by Golgi tendon organs) gradually adapt, allowing the body to safely generate more force.

These changes explain why strength often improves quickly early in training, even when physical appearance remains largely the same.

Phase 2: Muscle Hypertrophy and Adipose Tissue Adaptation (Weeks 6–8+)

After neurological improvements have laid the groundwork, structural changes become more prominent.

- Muscle Hypertrophy: Progressive overload damages muscle fibers at a microscopic level. The repair process strengthens and enlarges these fibers, resulting in greater muscle mass and force production.

- Connective Tissue Adaptation: Tendons, ligaments, and supporting structures adapt to handle heavier loads, improving joint stability and reducing injury risk.

- Adipose Tissue Remodeling: Strength training impacts not only muscle but also body fat composition:

-

-

- White Adipose Tissue (WAT): This is the primary fat storage tissue, serving as the body’s main energy reserve. Excess WAT, particularly around the abdomen (visceral fat), can obscure muscle definition, even if the muscles beneath are well-developed.

-

- Beige and Brown Adipose Tissue (BAT): Unlike WAT, brown and beige fat are metabolically active, helping burn energy to produce heat. Strength training, when paired with aerobic exercise, can promote the “browning” of white fat (converting some WAT into beige adipose tissue), which is more metabolically efficient.

-

- Impact on Visible Abs: Increasing lean muscle mass while improving fat metabolism gradually lowers body fat percentage. As WAT decreases and muscle size increases, abdominal definition becomes more visible.

-

Why You Don’t Have Abs Yet—and Why That’s Normal

Visible abdominal muscles depend on both adequate muscle development and reduced subcutaneous and visceral fat levels. Achieving this balance requires consistent resistance training, proper nutrition, including sufficient intake of healthy fats like monounsaturated (MUFAs) and polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs), and, importantly, patience.

The initial weeks of training primarily strengthen neural connections, preparing the body for future muscle growth and fat loss. These early adaptations form the essential foundation for long-term changes in physique, performance, and metabolic health.

Summary of Early Adaptations in Strength Training

| Time Frame | Primary Adaptations | Observable Changes |

| 0–6 weeks | Neurological efficiency (motor unit recruitment, coordination) | Rapid strength gains, better technique |

| ~6–8 weeks | Beginning hypertrophy, connective tissue strengthening, early fat adaptation | Slight increases in muscle size, improved control |

| 8–12+ weeks | Pronounced hypertrophy, WAT reduction, beige fat activation | Noticeable muscle growth, better body composition |

| Ongoing | Continued hypertrophy, fat remodeling, bone density gains | Visible definition, improved athletic performance |

Image from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5983157/

References

- Klein S. What Are “Newbie Gains” in Strength Training and How Long Do They Last? @onepeloton. Published April 3, 2025. Accessed August 6, 2025. https://www.onepeloton.com/blog/newbie-gains

- Rong W, Geok SK, Samsudin S, Zhao Y, Ma H, Zhang X. Effects of Strength Training on Neuromuscular Adaptations in the Development of Maximal Strength: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Scientific Reports. 2025;15(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03070-z

- Hughes DC, Ellefsen S, Baar K. Adaptations to Endurance and Strength Training. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2018;8(6). doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a029769